70 Years of The Quiet Man: Reassessing its Release and Reception in Ireland

Marking 70 years since the release of John Ford's influential and divisive drama, Sam Manning looks back on the film’s release in 1952.

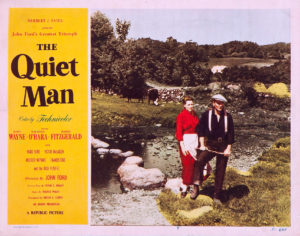

This year marks the 70th anniversary of The Quiet Man, the story of Irish-born American ex-prize fighter Sean Thornton (John Wayne) who returns to his native village of Innisfree, where he falls for Mary Kate Danaher (Maureen O’Hara). The Quiet Man is loved by millions but also repeatedly criticised for director John Ford’s stereotyped and idealised depiction of rural Ireland. Even if The Quiet Man provides an inaccurate portrayal of Irish life in the 1920s, it is a hugely significant cultural product that has remained in the popular consciousness for seventy years and still draws hordes of tourists to Cong, the small village straddling the border between County Galway and County Mayo which provided the location for many of the film’s exterior shots. While much has been written about the film’s production, reputation and legacy, this anniversary provides an opportunity to look at the film’s release and reception and consider its screening in Irish cinemas and the response of contemporary critics and audiences.

POMP AND CEREMONY

Following press previews, the world premiere of The Quiet Man was held simultaneously in London and Dublin on 6 June 1952. Among the guests for the latter screening at the 2,300-seat Adelphi cinema were President Seán T. O’Kelly and Maurice Walsh, writer of the short story on which the film was based. Many reports emphasised the pomp and ceremony of the occasion, with British trade journal Kinematograph Weekly observing that ‘thousands of people queued to obtain permission and it was necessary to turn away hundreds of people who could not be accommodated’.

The Adelphi’s general manager later sent a telegram to Republic, the film’s production and distribution company, claiming the event as an ‘enormous success. Acclaimed by every section of the public… Described as a breath of fresh air even in the green isle of Eire’. For those unable to attend the premiere, interviews with guests and patrons were later broadcast as part of a special 30-minute programme on Radio Eireann.

Following the premiere, the film was then exhibited at the Adelphi for a further seven weeks, where it broke house records and even attracted huge audiences during a summer heatwave. The success of The Quiet Man in Dublin led Republic to hold a showmanship panel, at which exhibitors were invited to share ideas of how they could promote the film at other cinemas. The panel’s suggestions included the use of a shamrock motif in foyer displays, a scenic snapshot competition and encouraging exhibitors to make connections with local Catholic clergy.

However, the star power of John Wayne, combined with the fact that films with an Irish connection were traditionally popular with local audiences, was enough to draw patrons away from their homes and into the cinema. It also entered theatres long before the introduction of RTÉ when going to the pictures was the most popular commercial leisure activity and part of many citizens’ regular social schedules. In 1952, 49.1 million cinema admissions were recorded in the Republic of Ireland and patrons could choose from 345 permanent venues with a collective seating capacity of approximately 200,000. In the same year, 28 million admissions were recorded in Northern Ireland, the majority of these in Belfast cinemas.

GENERALISATION

Irish critics generally praised The Quiet Man’s humour and entertainment value, believing that it would find favour both with American audiences who would enjoy the film’s romanticised depiction of Ireland and with domestic audiences who would take the film with a pinch of salt. The Irish Independent, for instance, claimed that it ‘should give great delight to… audiences in Boston and Philadelphia. As for us, we can afford a laugh too—even in the wrong places’. The Irish Examiner added that ‘John Ford rather generalises, but the generalisation is so pleasantly funny that we accept all this… It’s the finest bit of divarshun the Hollywood blarney factory has poured out’. This view was reaffirmed by the Connacht Sentinel, which reported that although The Quiet Man was a staged version of Ireland ‘it is all done in such a rollicking, happy-go-lucky atmosphere that no one could very well take umbrage’.

Harris Deans of the Belfast Telegraph added that it ‘may not be the real Ireland—just as Westerns are not the true America—but it is joyous entertainment for those who don’t take their nationality too seriously’. Given that The Quiet Man was by far the most successful film of 1952 in Belfast, it appears that many northern viewers held the same opinion.

IN THE CINEMAS

It was first shown at the Ritz, the city’s largest and most upmarket cinema, where it generated £24,000 from the sale of 195,000 tickets. During its fourth week, the film was supported by Irish Symphony, a documentary about Irish workers, and a fashion display of local linen organised by the Irish Fashion Guild, which involved ‘a team of mannequins, drawn from a Belfast agency, [who] presented 43 models in 20 minutes’.

From August 1952 to April 1953, the film played at fifteen Belfast cinemas, with admissions totalling at least 310,000 across all venues. The fact that the city’s population totalled 440,000 shows the attraction of The Quiet Man to Belfast residents, with the film’s depiction of Ireland appealing to people both from nationalist and unionist backgrounds.

Belfast writer John Campbell later recalled the film’s cultural impact, remembering that ‘male cinema goers squared their shoulders and swelled their chests as they identified with John Wayne when he hauled Maureen O’Hara across meadow and field in the scene which culminated in an angry and bloody confrontation with… Victor McLaglan, who had been foolish enough to cast aspersions on John’s masculinity’.

Contemporary views from ordinary cinema-goers are harder to ascertain, but some indication was provided by the Nationalist and Leinster Times which reported that ‘opinions on the film varied from the frankly enthusiastic to the downright condemnatory, from the people who loved every minute of it to those who thought the picture should never have been made or shown in Ireland’. One man was quoted as saying that ‘the picture is meant to be funny, and nobody is going to think that the Irish in the West or elsewhere really live and act like they did in The Quiet Man’.

Long queues and full houses were reported in all parts of Ireland. Limerick’s Lyric cinema ‘was packed to capacity from the first of the separate performances… Audiences will see it right through without the interruptions and slight disturbances which are part and parcel of the continuous performance. This is the first occasion in almost fifteen years that separate programmes have been the policy at the Lyric’. These separate programmes, where audiences had to arrive and leave at fixed times rather than enter as they pleased, allowed the cinema to maximise revenue and make the most of the film’s popularity.

At Carlow’s 1,000-seat Ritz cinema, The Quiet Man attracted 6,300 patrons over the course of only two days, with people travelling from neighbouring towns such as Athy, Portarlington, Abbyleix and Castledermot. The desire to see the film even led to court appearances and John Gallagher of Charlestown was fined £3 2s 6d for travelling to a screening of the film in an untaxed car. Police were called to keep order at some showings and, on 19 February 1953, the Royal Ulster Constabulary visited Enniskillen’s Regal cinema to discover an overcrowded venue with people sitting on steps and standing in passageways. A police sergeant stated that these violations ‘constituted a grave danger to the public attending the cinema and in the unfortunate event of an outbreak or fire or panic of any sort would lead, in all probability, to serious loss of life’. It is fortunate that no such incident occurred.

CULTURAL IMPACT

The film’s immediate cultural impact was also observed in France, where one Dublin journalist, upon returning from an assignment in Paris, stated that peaked caps were now being referred to as the ‘Quiet Man cap’. And many fans of The Quiet Man wanted to see the sites where it was filmed, with reports of visitors from Britain, France, Sweden and the United States. In August 1952, only two months after its premiere, an English film critic visited Connemara ‘in fulfilment of a promise made to himself immediately after he had seen the press-showing of the film in London’.

By June 1953, the Evening Herald reported that Cong was ‘having an unprecedented influx of foreign visitors this season’. This was clearly linked to the film as ‘one motoring party stopped to inquire for the road to Innisfree while an American woman writer arrived wearing a “Maureen O’Hara shawl”’. But not everyone was so positive about the 14,000 tourists who arrived in Cong that year with one Catholic Standard reporter stating that they could not bring themselves ‘to offer a sincere cead mile failte to the tourist who may come seeking the Emerald Isle of this picture’.

By the end of 1953, a year and a half after its release, The Quiet Man was still being shown and re-shown in cinemas across Ireland. In December, Belfast’s Curzon cinema advertised ‘positively the last showing of this film before being withdrawn. Don’t miss the opportunity—you know it’s worth seeing again!’ And given the large viewing figures, it is likely that many people saw the film on several occasions. Cinema re-releases, television screenings and home media releases have also provided further opportunities both for repeat viewings and for subsequent generations to discover the film. And seventy years on from the film’s original release, tourists still flock to Cong to visit the film’s locations, The Quiet Man Museum and the statue of John Wayne holding Maureen O’Hara aloft.

Many thanks to Des McHale for the use of images in this article.