Wartime Cinema-Going and the Belfast Blitz: Part 1

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Belfast during WWII, Sam Manning looks back on cinemas in Belfast and how they prepared for the coming blitz.

Part 1: The City Waits.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the UK Home Office ordered the closure of cinemas and other places of entertainment as a safety precaution until they could judge the potential scale of attacks. Soon after this announcement, cinema exhibitors in Northern Ireland met with representatives of the Ministry of Home Affairs at Stormont, which then quickly issued a ruling that cinemas and theatres should remain open in the province. Although cinemas soon reopened in Great Britain, this incident provides just one example of how Northern Ireland was a place apart from the rest of the United Kingdom.

Its participation in the war and the impact of the Blitz, however, meant that that the experiences of Belfast citizens were more similar to residents of British port cities such as Bristol, Cardiff or Portsmouth than to those in smaller Ulster towns such as Banbridge, Cookstown or Portrush. And Northern Ireland’s participation in the war, furthermore, distinguished it from its southern neighbour, which remained neutral during what the Irish government euphemistically labelled ‘the Emergency’.

The 80th anniversary of the Belfast Blitz provides an opportunity to explore the impact of the war on the city’s cinemas. The destruction of three cinemas and the temporary closure of several others was relatively insignificant in comparison to the lives lost and the overall damage done to the city. Nonetheless, cinemas were important social spaces providing escapism, entertainment, and education during one of the most difficult times in Belfast’s history.

The 1930s witnessed a cinema building boom as art deco picture palaces such as the Majestic, the Ritz and the Strand were constructed across the city. By the beginning of the war there were over 40 cinemas in Belfast and a trip to the pictures was firmly entrenched as the most popular commercial leisure activity. Cinema-going habits were deeply embedded in everyday routines and it is therefore no surprise that that the tumultuous events of the Second World War altered people’s cinema-going habits, the films they watched and they ways they responded to them. A greater desire for relaxation and reduced competition from alternative leisure pursuits are just some of the factors that led to a dramatic increase in cinema attendance, with UK admissions rising from 990 million in 1939 to almost 1.6 billion in 1946.

In the early years of the war, the threat of German bombs meant that even with the compulsory introduction of fully trained fire watchers and fire-fighting equipment, the act of watching a film in a tightly packed space became a potentially life-threatening activity. But even the enforcement of a blackout and restrictions on the levels of external lighting for cinema did not deter patrons. Press reports during the early months of the war suggested that audiences were increasing and queues were forming at both afternoon and evening screenings.

Despite new challenges, such as shortages of projector carbons and the late arrival of film reels from Great Britain, exhibitors remained optimistic that business would continue to grow during the conflict. They adapted quickly to wartime conditions and many venues did what they could to help with the war effort.

For instance, Hippodrome manager Guy Luther Birch erected an elaborate foyer display to help raise money for the Ulster Spitfire Fund. He also regularly entertained troops at his cinema and made sure that any wounded soldier never paid for admission. Other managers raised money from ‘Midnight Matinee’ charity screenings and arranged collections of cigarettes for soldiers and sailors in the local area.

Cinemas also took on a new purpose, transforming into spaces to educate people on air raid precautions. In July 1940, thousands of citizens attended eight cinemas across the city where lectures organised by the Belfast Civil Defence Authority were given on what to do in the event of a German attack.

At the Ritz, Belfast’s largest cinema, Minister of Public Security John MacDermott told the audience that he ‘did not know how long would be the breathing space before there was an air raid, but they must be prepared for it’. The beginning of night bombing campaigns in British cities, such as the Coventry attack in November 1940, meant that similar events were held the following April.

At these lectures audiences were told what to do in the event of a raid, how bombs should be tackled and what protective measures may help during an attack. Attendees were advised to wear gas masks, but several reports suggested most people did not take such precautions. In the week following the lectures one cinema manager even offered free admission to anyone carrying a mask, which, according to him, was ‘just to see how many free seats he would have to provide’. One Belfast News-Letter reader suggested further measures, believing that cinema managers ‘should follow the example set by their colleagues in England and refuse admittance to people who are not in possession of respirators’.

But what was it like to visit a Belfast cinema in the early stages of the war? The diaries of Moya Woodside (b. 1907), written as part of the Mass-Observation social research project, provide an insight into the habits and responses of one particular wartime cinema-goer. In March 1940, Moya observed the growing attendance at cinemas, stating that they ‘must be making their fortune out of the war, offering as they do warmth, entertainment, and somewhere to go for thousands of bored soldiers and evacuees’. On a cinema trip later that year, she visited three sold out city centre venues before buying a ticket for one of the last and most expensive seats at a fourth. ‘Usual boring newsreel’ she commented, ‘received by the audience in the apathetic silence it deserved’.

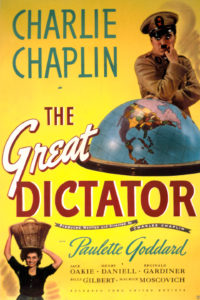

In January 1941 The Great Dictator, Charlie Chaplin’s satire of Adolf Hitler, was released in Belfast cinemas. Trade journal Kinematograph Weekly reported that both the Classic and the Picture House ‘were completely swamped out the opening day, and had to hang up their telephones as they were unable to cope with the queries for booked seats covering the whole run of the film’. Many of those turned away from these screenings had travelled from Éire, where censor Richard Hayes banned the film fearing that its exhibition would lead to ‘riots and bloodshed’. Even adverts for screenings north of the border were barred from Dublin newspapers.

In spite of its popularity, Moya Woodside found it an ‘uneven film’ praising the famous final speech and the iconic globe balloon scene, yet at the same time commenting that the ‘ghetto and persecution seems sentimental, theatrical and unconvincing’. She added that towards the end of the film ‘people were putting on their coats and generally getting ready to go, not paying much attention—mentally to the screen. I hope that the case for tolerance will stick in people’s minds but I doubt it’.

By 1941, air raid sirens were a regular occurrence at cinema screenings and slides were often shown on the screen stating either ‘alert’ or ‘all clear’. The interruption of air raid sirens often led to protests from cinemagoers about missing the show or not receiving refunds from cinema management. These complaints, however, did not deter the cinema trade from preparing for a potential air raid. In response to the growing threat of an aerial attack the Astoria even adapted its underground space for use as an air raid shelter.

In February, 200 cinema employees from across Belfast, including managers, usherettes, commissionaires and cashiers were present at an incendiary bomb demonstration held at the rear of the Picture House, Royal Avenue. After RAF men exploded bombs and auxiliary firemen demonstrated their equipment, volunteers then ‘came forward and dealt with bombs fired inside a small building and in the open’.