Watching the North – Images Can Kill: The Writing on the Wall

Ruairí McCann's Watching The North column returns with an examination of Armand Gatti's little known experimental drama filmed with the people of Derry in 1983.

There’s a revealing moment in Margo Harkin’s 2018 documentary Eamonn McCann: A Long March, when the two old friends and veteran radicals, McCann and Bernadette Devlin, casually mull over a longstanding sore point.

Why is it that a popular non-sectarian, socialist, working-class movement failed to take hold in Northern Ireland, beyond its powerful yet fleeting moment on the barricades in the early 70s? McCann offers one speculation, that on top of all the outside forces that prevented it, the movement lacked vision. In the sense that they zeroed in on immediate injustices, such as discrimination in housing and voting rights, at the expense of time needed to develop and transmit a clear vision of a future beyond the struggle. Republicanism and loyalism, in their various shades, would come to offer more robust prognostications and icons.

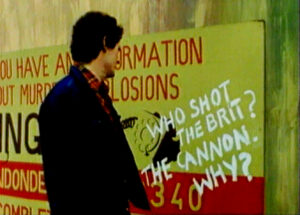

Nous étions tous des noms d'arbres (1983) or The Writing on the Wall is a film that addresses this impoverishment, directly and as a “battle of images” as intoned in the beginning. It’s a film deeply interested in the intersection between history, politics, and fiction, exploring how the latter can be a revealing prism through which the former two conundrums can be understood and perhaps even transformed. This visionary approach to depicting reality through cinema was in many ways, defined and played out by ordinary people in Derry, where this experimental production took place.

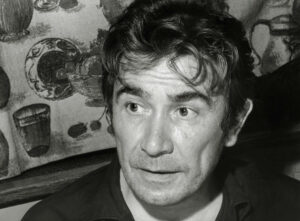

The catalyst for this experiment was an outsider; the French film and theatre maker, wandering troubadour and troublemaker, Armand Gatti.

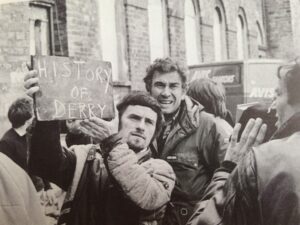

Gatti first came to Northern Ireland in 1981, on a temporary residency at the Lyric Theatre in Belfast. His interest in the conflict in the North deepened first hand, and then became a creative impulse when he paid a visit to Derry. The city’s working class, underdog character, and how it’s strong, albeit fractured and warring, awareness of its history (recent, ancient, and mythic) was not only evident, but plastered on almost every wall in the forms of graffiti and murals, appealed to Gatti’s twin sensibilities, as a social realist and someone deeply invested in the magic-like power of images. After encountering the civil rights activist Paddy ‘Bogside’ Doherty and the cross-community ethos and practices of the Derry Youth & Community Workshop, all the players and the pieces were in place.

On Doherty’s suggestion of a collaboration, Gatti proposed an unusual project. A period of collective discussions, poster and collage making and then script writing, culminating in the making of a film that would not only be about the Workshop, their lives and concerns, but also a work of fiction. Constructed and played out by them using an experimental methodology that Gatti had developed over the preceding decade in the theatre. A semi-improvisational approach, where a cast of non-actors create their own parts, contribute to the plot using material from both their own lives and imaginings, write their own dialogue and then act it all out, with Gatti serving more as a creative auditor than the domineering author.

The film that emerged out of this process is a wonderful, barbed patchwork and an equalitarian ensemble piece. Set in Derry, engulfed in the combustive atmosphere of the 1981 hunger strike, the knot of shaggy dog tales begins with a symbolic weapons exchange. The Workshop recovers a centuries old cannon from the wreck of a Spanish galleon, just as a revolver, owned by a tutor, goes mysteriously missing. Likely stolen by one of the older Workshop kids, several of whom are involved in a haphazard bombing scheme.

This parallel sets up the plot but also the first of many metaphors, from full set pieces to glancing shots that overlap and collapse the past and the present. This linking of a conflict centuries ago with the one still ongoing is not just a pointed political statement but a creative evocation of the the day-in and day-out, psychological tightrope walk that is living in a city and country in dispute, where history and the present moment constantly, intensely co-exist with both symbolic and violently material consequences.

The cannon is exhumed from its watery grave for less violent and more symbolic purposes, as the centrepiece in an ambitious, role-playing exercise. A parable rooted in fact, to be devised and delivered by the kids of the workshop—all from working & lower middle class catholic and protestant families —guided by the magnetic, wizard-like presence of Seamus Doherty (Paddy Doherty essentially playing himself) and observed by Eamonn. A sceptical and slightly bumbling, visiting American scholar, played by the local, but experienced, actor John Keegan, a mainstay of the Lyric stage in the 1970s and 80s.

The goal is to achieve some cross-community and historical understanding, and the means are a fantastical, mnemonic play with the subject being that most theatrical of Irish rituals, a funeral. The students are to represent the different political forces—cast against type, so to speak, with Catholics from the Bogside playing the Army and protestants from Waterside playing the IRA and so on—and tasked with sussing out the best way to bury a British soldier, or rather not just any British soldier, but a specific individual. A young Englishman from a catholic family, who died in a fire while rescuing a local catholic woman and her children.

This soon attracts the attention of a nearby British army command, the “neighbours across the way”. Their interference infects the roleplay and changes its course. Fiction starts to become reality, with the exercise getting out of hand and the revolver reappearing and leaving another soldier dead. The film’s already symbolistic nature, expressed especially in much of the dialogue, starts to overwhelm its realism as things fall apart and careen towards some great cultural happening, exorcism, and tragedy.

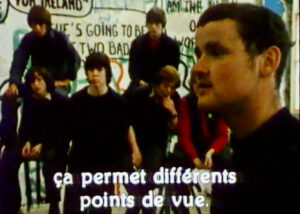

The early scenes of preparation are some of the film’s richest. Shot in an immediate handheld style, with the young non-actors flexing excitedly, and excitingly, between being overt performers, documentary subjects and a blurred in-between. It is a chaotic, impassioned and often funny group chorus on the embattled theme of ‘identity’, for the laying down and arguing over of the rules of this roleplay very quickly becomes a verbal war that moves fluidly across the supposedly clearly delineated zone. At some points in these discussions, the babble descends in the usual ‘us vs. them’ rhetoric.

Other times, these hard and fast categories don’t cut it, like when one protestant kid says he hates the army and resents the assumed allegiance. Another states that she is from an Irish catholic family, but her father is an immigrant labourer who raised them partly in England, giving her a combination of accent and religion that has isolated her from either community. When the American butts in, criticising their choice of subject, a catholic soldier who died accidentally while performing a heroic deed, as an easy, uncontroversial route, he’s greeted with jeers from all sides. It takes an instance of yankee chauvinism to show that common ground is possible, if even just for a moment.

In sharp contrast to the unstudied liveliness of the workshop scenes are those set in the British army command monitoring the city and their role-play. Here the film veers away from documentary and towards something like science fiction, with HQ rendered as a cold and sterile inhuman space. A controlled array of flickering screens, humming computers and highly stylised, stiff upper lip performances, epitomised in the wry and sinister figure of Mr. Bond (Des McAleer). It’s a funny and disturbing depiction of power on high, its simultaneous remoteness and invasiveness.

For those represented in this panopticon; the upper classes, the military and landed gentry, society is a prison, to be highly regimented. For those in the workshop, damage control is to be replaced with creative explosions, the prison with a game with a never-ending number of arrangements and rewards.

Nous étions… strange mixture stems from its director’s unusual background, his various points of connection and disconnection with Northern Irish society and politics and the fertile state of a nascent, independent Northern Irish cinema.

Gatti would have found the political instability of the North familiar, but he was the perfect outsider observer to its ethno-religious balkanization. He was raised in an atmosphere of secular, radical politics, countered from the outside by limitation, violence and expulsion, as the son of a militant anarchist whose activities required a peripatetic existence. This uprootedness—Gatti was nearly born an American, was actually born in Monaco, of Italian parentage but raised in Southern France—became essential to his sense of self, politics and artistry. He once stated that he saw himself as neither Italian nor French but as an “immigrant’s son”. He also declared himself an internationalist, stating with some detectable pride in Welcome to Our Battle of Images (2009), critic and filmmaker Fergus Daly’s short portrait of Gatti, that he never made a film in the same country twice.

Gatti’s observations of Northern Ireland were also fed by his formative experiences in World War 2, where he was a teenage resistance fighter, spent over a year in a Hamburg concentration camp and then after a daring escape, briefly fought as part of the British SAS. These experiences not only cemented an inclination towards insurgent left-wing politics and art, but also made him unusually sympathetic across the lines of conflict. He found parallels in his experience in Hamburg with those of the IRA prisoners in The Maze.

Specifically, how he and his fellow prisoners used French as a secret code and form of bonding, similar to the use of Irish in the H Block. The connection would flower into two French-language plays, Le Labyrinthe (1982) and Le labyrinthe tel qu’il a été écrit par les habitants de l’histoire de Derry (1983), written and staged in tandem with the production of Nous étions… and the final months of the hunger strike campaign. And yet, as an ex-member of the British armed forces, he sympathised deeply with the average serviceman on the street and made radical extrapolations from that empathy.

This manifests in Nous etíons… when the father of the dead soldier visits the Workshop. A rare scene of mournful disquiet, in an otherwise helter skelter film. At one point the father says that his son joined the army not out of patriotism but for want of a job, which Gatti answers with a shot of a sign that states ‘Irish Worker = English Worker’.

This wandering agitator landed in a hothouse period of independent Northern Irish, and Irish, cinema, where many were seeking out new ways of translating The Troubles, and its ripples, on screen. Perhaps the (currently) most seen and esteemed example was made in Belfast; Pat Murphy and John Davies’s experimental narrative film Maeve (1981), which also stars Keegan as a kind of devil’s advocate, though one from closer to home and so more emotionally fraught.

However, Derry also served as a key stage. There’s Colm Villa’s dyspeptic genre film Open Asylum (filmed in 1980, completed and screened in 1982) about an unaligned protestant railroad worker (Villa) exploited and chewed up by all sides of the conflict. Commissioned by Channel 4, the Welsh filmmaker Karl Francis made Chekhov in Derry (1983), a documentary charting Brian Friel and Stephen Rea’s restaging of Chekhov’s Three Sisters in the Guildhall. An astute meditation on the need to open up new artistic outlets, to find new expression, within a constricting political situation. Channel 4 would also fund one of said outlets, with the founding of the Derry Film & Video Workshop in 1984.

Out of this hive of self-reflexive, countercultural filmmaking, Nous etions… is one of the most ambitious, in depicting art, history and the making and the breaking of society as dramatic, unaccountable, living forces.

An extract of Fergus Daly's Welcome To Our Battle of Images can be seen here.