A Criminal History of Cinemas in Northern Ireland: Part II: Robberies and Raucous Rowdiness

Most criminal incidents, however, were unrelated to what was projected on the screen and the large amounts of money held by cinemas made them prime sites for theft and robbery.

In 1933, for instance, a ‘mysterious robbery’ occurred at the Derry Picture Palace. Despite widespread inquiries, the police were unable to find the culprit or recover the money box containing the day’s takings. The new picture palaces that opened during the 1930s were popular targets for criminals. Just one month after the opening of the Troxy on Belfast’s Shore Road, Robert Stewart broke into the cinema office, blew up the safe and stole £58. Sentencing Stewart to three year’s penal servitude, the judge stated it was a ‘professional job’ and that he ‘had been in and out of gaol since 1915’. Safe robberies continued into the post-war years and in 1951 James Kennedy broke into the Stadium cinema and stole £126. After matching samples of glass, wood and putty were discovered on his clothes, Stewart was also sentenced to three year’s penal servitude.

While money was the most prized asset, thieves also targeted the confectionary and cigarettes sold on site. In 1937, for example, John Lennon admitted breaking into Belfast’s Strand cinema, stealing 10,000 cigarettes, a pair of gold cuff links and a raincoat. Juveniles often targeted cinemas for items other than money, such as the three boys who in 1936 were charged at Belfast Children’s Court with breaking into the Sandro cinema on Sandy Row and stealing around 250 admission tickets.

Overseas visitors also targeted Northern Ireland cinemas. In 1944, Canadian sailor Harvey Merrifield was charged with the theft of a thermometer from a Derry cinema. When fining the defendant 21 shillings, the Resident Magistrate stated that ‘some Canadians had developed a craze for this “souvenir” lifting’.

Children and teenagers were often accused of raucous behaviour within cinemas, and this sometimes crossed the line from innocent fun to criminal activity. In 1928, John Wilson threw a stink bomb into the auditorium of the Queen’s Picture Theatre leading several people to leave the hall as they were ‘sickened by the smell’. During the 1930s, small explosives known as squibs were a source of concern for cinema exhibitors. After two young men were fined for throwing squibs into the Gaiety cinema, The Bioscope reported that magistrates ‘intend to deal severely with any further offenders, owing to the fact that serious consequences might ensue’. By 1936, there were further prosecutions and a report observed that the ‘squib nuisance in some Belfast kinemas is becoming intolerable’.

Criminal damage to venues placed an extra financial burden on cinema managers. In 1943, for instance, a 12-year-old boy was put under probation at Belfast Juvenile Court for maliciously damaging a seat at the Broadway cinema. The owner stated that in ‘the past year 576 seats had been slashed in the Broadway’ adding that six members of this staff were ‘specially trained for the prevention of vandalism’. In 1954, a 16-sixteen-year-old boy threw a bottle at the Stadium’s brand-new CinemaScope screen, causing damage estimated at £500. He was given a conditional discharge and asked to pay £10 compensation and 30 shillings in costs.

Rowdy behaviour sometimes led to attacks on cinema staff. In 1929, John Leitch was fined for assaulting an attendant at Belfast’s Midland Picture House, located in the York Street area of north Belfast. The Bioscope commented that ‘Belfast magistrates are determined to see that the good order for which local picture houses are noted is not going to be disturbed by rowdies, who take a delight in trying to cause trouble and then, when asked to behave themselves, assault attendants’. Similar incidents continued into the 1960s, when five men admitted charges of assault, disorderly behaviour and malicious damage at the Clonard cinema. After one of the men was thrown out by the cinema staff, he returned with his three brothers and another man, and then hit one of the attendants on the head with a hurling stick.

From the 1950s, reports of rowdy behaviour reflected moral panics, public concern surrounding teenagers and emerging subcultures such as Teddy Boys. In 1954, Police Head Constable McMullan told Belfast Custody Court that ‘cinemas in the district were “plagued” by rowdyism, and that decent people were almost afraid to go into them in case they might become involved’. Four years later, these complaints still persisted, and Resident Magistrate J.V.S. Mills claimed that there ‘is far too much rowdyism in certain suburban and downtown cinemas’. By 1960, the Belfast Telegraph’s ‘Youthbeat’ column reported on ‘rowdies in the cinema’ engaging in gang fights, brawls and seat slashing. It commented that damage was caused by both sexes and ‘trouble crops up no matter what is on the screen’.

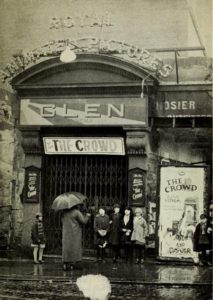

But cinema management and staff were sometimes the perpetrators of crime. Some cinema workers stole from their places of employment and several managers were prosecuted for tax fraud. However, a greater number of prosecutions were related to overcrowding and fire safety, a particular source of concern given the use of highly inflammable nitrate film stock until the 1940s. And safety concerns were heighted after the 1929 Glen Cinema disaster, in which a smoking reel and the resulting panic led to 71 deaths in a Scottish cinema.

In 1930, the management of the Midland cinema were fined £3 for permitting overcrowding in the building’s passages and staircases. The prosecutor stated while he did not want to impose an exaggerated penalty, ‘it was only right to point out that horrible disasters had occurred in houses of this description, and the exit should at all times be absolutely unobstructed’. In 1932, William Barry, the proprietor of Strabane’s Palindrome cinema was fined 10 shillings for permitting overcrowding and providing six people with chairs in a side passage. A District Inspector told Strabane Petty Sessions that ‘they all knew how serious questions of that nature were, and the terrible calamities that had occurred owing to the regulations not being complied with’.

This article covers only a small selection of criminal activity reported in newspapers and trade journals. There are surely many other crimes that left behind no historical traces and went unreported or unprosecuted. Several themes emerge from the reports, leading to further questions about the nature of criminal activity.

Firstly, I’ve often heard stories of female cinemagoers carrying safety pins to ward off unwanted male attention. Is it possible therefore that these darkened spaces also provided places for sexual assault or harassment? Secondly, the vast majority of reported crimes were committed by men. Were they simply more likely to commit crimes or did female crime go undetected?

Finally, there are several reports describing people of ‘no fixed abode’, leading us to think about how poverty and deprivation may have led people to commit these crimes.

Cinema crime peaked when there was an abundance of cinemas and lots of people going to them. As cinemas started to close down in large numbers from the late-1950s onwards, the number of reported crimes also declined significantly. In the period from the 1920s to the 1960s going to the cinema was far from a dangerous activity. Cinema-going experiences were overwhelmingly positive and most nights at the pictures ended without any major incident. But the examples discussed here show that cinemas in Northern Ireland were not immune from criminal behaviour. And cinema exhibitors then faced a new set of challenges after the outbreak of the Troubles.