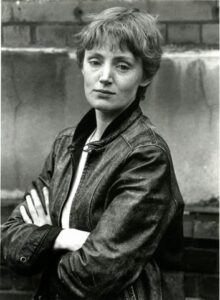

Watching the North – Margo Harkin

To mark the release of her latest film 'Stolen', Ruairí McCann spoke to Margo Harkin about her early cinema memories, her long career in film and the connections between her early films and this latest work.

‘The Fifth Province’ – An Interview with Margo Harkin

John Akomfrah of the Black Audio Film Collective once stated that the first step towards achieving the political representation is to find a response to the question, “Who do you think you are?” with the exploration of new, iconoclastic approaches to art being one potential fertile vessel for answers. This chimes with the inception of Field Day Theatre Company which was launched in Derry in 1980. Its ambitions were summed in the phrase ‘fifth province’ meaning that the inequities and deadlocks that limited the political and social hopes of the actual, four geographic provinces of Ireland could be imaginatively reckoned with, countered, and perhaps overcome on the plane of the imagination and performance.

As a writer and a curator interested in both cinema and radical politics, their intersections and how they can inform each other, I’m always eager to encounter a similar zone of political contention and revelation within Irish cinema—and to some degree, this column has been a record of several instances where this notion, implicitly or explicitly, has flared.

The film and television work of Margo Harkin most definitely resides on this province. Right from the beginning, as a key member of the Derry Film & Video Workshop, founded in 1983 by Harkin, filmmaker Anne Crilly and visual artist Trisha Ziff as a feminist and socialist counterforce to the North’s dominant image regime, maintained by the British media establishment. It culminated in Crilly’s documentary Mother Ireland (completed in 1988 but not shown until 1991) and Harkin’s debut film, and exemplar of fusing serious political intent with drama and an adventurous film style, Hush-A-Bye Baby (1990)

Since Derry Film & Video’s dissolution in 1990, Harkin has consistently demonstrated, and continues to explore, moving images as a bottom-tool of history and personal expression. Right up to her latest film, Stolen (2023), which is set to screen at the Queen’s Film Theatre on June 21st as part of Docs Ireland. Harkin described it is both as a personal and a much-needed series of first-hand accounts, venting and confronting experiences of Ireland’s notorious network of Mother & Baby Homes.

I spoke with Harkin about the film, along with her first experiences of cinema, her memories of Field Day, Derry Film & Video, several of her films, and her point of view as a political artist.

I think a good place to start is with your first experiences with cinema as a child. Do you have any early moviegoing memories that kind of stick out for you in particular?

I come from a very large family, my mother had sixteen children, and she also worked. My father was from the Bogside in Derry. They had this thing called the Clubs where they sold shoes out of my Granny Harkin’s house. They lived at my granny’s house at the start, and later they bought a farm and a big house out in Drumahoe, which is about three miles outside of Derry. They still carried on this business in the Bogside for a while and so, when they were doing that, on a Saturday, you know, when we weren’t at school, we would be given money to go down to The City Picture House on William Street, near Rossville Street which was the street where most of the riots happened and where most of the engagement happened with the British Army, many years later. It was just an old fleapit type cinema you know. Always westerns, it was a diet of westerns. I’ve just memories of doing that, of going to this old cinema on a Saturday and we would be given money to get chips in the local chip shop as well. I mean that was a habit, that everybody went to the matinee on Saturday in the cinema. It was a practice among all sorts, especially ordinary working-class families.

The first film that really had an impact on me was 12 Angry Men. You will hear lots of people saying this, but it absolutely did, around the time it came out. I look back and I must have been incredibly young, but I remember it so well. I’m not saying I remembered the story so well at the time—well obviously I do now—but my mother and father both took me. We went to see it in the Rialto Cinema in Derry, and I remember us walking up this steep street and standing at Ferryquay Gate and my father talking about it, about this man doing the right thing against all the odds. It had a huge influence on me, you know. My father was very catholic. He had a very high moral sense. But that stayed with me, that despite other people trying to get you to follow the herd or fall in with the consensus, the majority point of view, you actually, if you believe in something, you should stand up for it, you know, and argue. The Henry Fonda character changed the whole jury around; it was an amazing film in that sense. And years later I read about things that the director Sidney Lumet did, like, as the film went on, he closed in the walls of the set to create more tension. So that still impacts on me. I’ve often thought if you were to make it now, you couldn’t have 12 Angry Men. I would like to make a film that was called 12 Angry Women *laughs* but it would be very different. But still, it was that whole thing about having a moral spine that really affected me at a young age. I had to be very young. I think I was about 9, maybe.

And the other one I remember was, my Granny Harkin and all her old women friends from about the Bogside, they used to go to the cinema a lot when a new film came out, and they took me sometimes. And I remember them taking me to see The King And I, and it absolutely had an amazing effect on me. I think it started my sexual awakening because Yul Brynner was just so, I don’t know, so sexual. But now I look back at him and think “Oh what a fucker he was” you know *laughs* He was such a domineering man but yeah that whole kind of gender stereotyping probably had an impact on me at that time, you know, this forceful dominant man and this woman who stood up to him. Insofar she was able to stand up, with the mores of that day. I just remember being thrilled by The King and I. It was so exotic. I’m sure it was nothing like it actually was depicted, whatever the kingdom was, but all these little children in incredible costumes. It just opened up… almost like a kind of, a magical realism… No, I wouldn’t call it realism because it was complete fantasy but there was a magic about it, a fabulousness that opened my eyes to what was possible with cinema. And there were lots of films over the years, but as a child those were the ones that impacted on me, you know.

And were the seeds of film as something you could do yourself, become a filmmaker yourself, planted around your teenage years?

No, absolutely not. I loved art. I loved drawing and painting at any opportunity. I was being brought up in this large family but any chance I got I would go into another world where I got out my big painting set, you know. I used to paint on the back of Bigger calendars. Bigger was an animal feed company, and my father was a farmer at the time, and he used to get gifts every Christmas of these big calendars. And to me they were a godsend because the back was a full, big white page *laughs* and I used them for painting on. So, I just loved art and you know. I wasn’t discouraged. I don’t think I was particularly encouraged but I wasn’t really discouraged, and so I always wanted to be an artist. That was it. Being a filmmaker never crossed my mind.

By the time I went to art college in Belfast, media studies didn’t exist, and film school was a distant thing away. I discovered while I was in art college that Pat Murphy [director of Maeve (1981)] had been just ahead of me. She would probably have been in the year ahead, although we’re much the same age, and she was in Belfast for a while and then she went to the Royal College of Art in London. I was aware of that, but it still didn’t occur to me that was something I could do. What happened was, when Channel 4 set up, by that stage I had become very politicised by what was going on in the North, and they gave an opportunity for unheard voices, silent voices as they called it, to be heard throughout Britain. But you had to bid. They were looking for a new seedbed of talent as well. By that stage, a few of us had come together, Anne Crilly, Trisha Ziff and myself, and we said “Let’s bid for this”. Originally, we were just a purely woman only workshop but it rapidly changed because there was just so many people wanting to get involved in it and we needed different skills and so we did gradually become a group of seven.

It was all to do with Channel 4. I’ve talked about it a lot you know but that particular moment in time was just remarkable. And it was done during Margaret Thatcher’s reign which always amazes me, because some of the most radical types of filmmaking were allowed to experiment during that period when she was actually trying to clamp down, trying to censor the media. And we did run into media censorship in the end with Mother Ireland, which was the first documentary we made for broadcast, which was written and directed by Anne Crilly and I produced it. So that was a big story, a really big story, about how it ended up that they wouldn’t show it. But they showed it two years later in a series called Banned.

Was that in 1991?

Yeah, yeah. She had to make all the cuts that had already been mostly negotiated beforehand, but we went around the country with that and toured with it and got an amazing reception like, because people said “What?! What are they banning this for?” It just pointed out the absurdity of the legislation.

I would like to wind back to a bit before Derry Film & Video because I was reading through the work you’ve done, and you worked for many years in theatre. It seems like that was a huge part of your life, and also you were involved with the Field Day Theatre Company. Could you talk about how Field Day specifically, or theatre in general, influenced you as a filmmaker?

I only really worked with Field Day. I hardly did any other work after that with anybody else. I knew Art Ó Briain who was the director of Field Day’s first play, Translations, written by Brian Friel, and he knew me from when I worked in this organization called Derry Youth & Community Workshop which was a big unemployment scheme in Derry where we would take all these young people who had no work. And you know we were supposed to be showing them skills and trying to stimulate unemployment, which was never going to happen. You really need serious investment and new skills training. What we were doing was puttering about and taking people off the streets you know. But I knew Art from that time because the Workshop used to do a lot of group work and he would come up from Dublin with other people for that. I loved him to bits like. Sadly he died three years ago.

One day I resigned from the workshop because I just got depressed about what we were doing, and I was in my back garden literally planting seeds, and I always think it was very metaphorical *laughs*. Apparently, I had left the front door open, and he came right through the house out into the garden, and he offered me this job as an assistant stage manager with Field Day. And I thought he was looking for me to do voluntary work. I would have been happy to do anything at that time and so I agreed, but in fact, I was paid and paid very well. You were paid Equity rates. And it was the most incredible experience, because I just met the most amazing people who really educated me a lot. It was an unbelievable endeavour to be involved with and it happened almost by accident. I don’t know if I would say it was accident or design or what, but the fact that I knew Art made all the difference. It changed my life really; I would say that. It changed my creative life, because when I came out of art college, most of my friends went on to teaching degrees and I didn’t want to do that. But I did end up teaching for a while and then had to force myself out of it, and I found it very hard to make a living. I was married by then, and my husband, Kevin, and I were really struggling trying to pay a mortgage. Sometimes I was just taking jobs just to earn money and I thought “Gee I’m never going to do what I want to do”. But this was the first time that I really got the opportunity to mix with people who were intellectually challenging and stimulating and highly creative and I just felt I was finally in a milieu I wanted to be in.

And I knew very little about theatre, I mean, I liked the theatre. I used to go to the theatre if I got a chance but there wasn’t much chance in Derry and especially during

Picture - Belfast Telegraph Archives

The Troubles. But that year was also a highly political year, 1980. 1980 was the year of the first hunger strike and 1981 was the year of the second hunger strike. I worked with Field Day, and we toured all around Ireland and it was just magic, electric. The audiences were flocking to it; and I don’t know that they particularly knew what it was they were going to see but I think they felt it was something expressing their life, their beliefs, their culture, that Brian Friel was that kind of writer who they hadn’t seen before. It was just such an exciting experience, mixed in with the complete *laughs* dreadfulness of the conditions that we worked under. We were showing the play in schools, and I had to go ahead and clean out, sometimes, like a tearoom or whatever and sometimes the actors had to change their clothes in the cloakroom that the kids had been in that day. So, there were dreadful conditions, but Field Day wanted to go to all the halls they could go to, or schools throughout Ireland, to as many places as possible.

So that was just an amazing experience, I can’t explain it enough. They all talked to you equally. Brian kind of took me under his wing because I was probably the only Derry person at the start but later on, the company manager asked for an assistant and Fionnuala O’Doherty joined us. She was from Derry too. We were the only Derry people. I went all around the country with them. I also had political views, which I expressed, about what was going on at the time, and I think they had a level of respect for that. I felt I was a ‘like’ thinker with them, in terms of the politics of the place. And that whole thing about them creating a ‘fifth province’, a ‘province of the imagination’ was hugely influential. Also, I remember that Stephen Rea in particular instilled in me that you should always strive to do things to the best of your ability, you should strive for perfection, and he was pretty damning about some of the other theatre practices in Ireland. He thought they, some companies, were sloppy. He said there was this phrase in Ireland “That’ll do” *laughs* that if you couldn’t get something right, that’ll do. He said to never accept that attitude and that has stayed with me, you know. I'm sure things have changed dramatically since. I know they have. But I’m pretty finicky and known for being finicky, and maybe I had an element of that in me, but I learned a lot with them.

So, I worked with the Field Day plays in the early days. I think I worked on four of them. After Translations I went to England and did The Theatre Design Course at Riverside studios with Percy (Margaret) Harris. Again that was a great experience, you know. That year in London I went to so many plays. Every week we’d go to two plays, maybe three, and it was in the Hammersmith Studios where Dance Umbrella happened, so I discovered I loved all that. And you were just meeting incredible people. So, Field Day opened up all of that to me, and I came back and designed then a few of the plays. But then the opportunity for the Derry Film & Video Workshop came up, and I kind of got absorbed with that, and became a filmmaker instead.

I saw this wonderful documentary about Field Day called Chekhov in Derry. It was made by Channel 4 in the early 80s.

Was that Karl Francis? I think that was Karl Francis. I would love to see that again. I appear in it briefly.

In that film, you see the combination of artistic rigour but also this political dimension, that it can be activism but also great artistic work, I can see that in your work.

Absolutely, absolutely. Like at the time, whenever they did Translations, I remember they used to put reviews up on the board and there was a very critical one from Edna Longley where she described the Field Day enterprise as being “old whines in new bottles” and she particularly always attacked Seamus Deane. Like, the board of that company was incredible, although it was all male and later that became a big, contentious issue. Other people gave amazing reviews, especially in England and in Dublin, but no, it didn’t go down so well everywhere in the North.

I remember when we went to Belfast’s Grand Opera House, it wasn’t booked out as it was in most other places. There were lots of empty seats. Brian was trying to speak to everybody but not everybody was interested. I had to get props for that play, and I went to the Ulster American Folk Park to get old bowls for the dresser and that type of thing. And always what would open the door would be when I would explain to people what this was for, and who was it for, and what the play was. They would just welcome you and be very helpful. The Folk Park staff had never heard of Brian Friel, *laughs* never heard of him. They were very helpful all the same. Our culture was just kind of split down the middle, in terms of Protestant and Catholic. Really, it was extraordinary. So yeah, I learned lots of lessons. And we had great parties, let me tell you that. We had fantastic times. Brian would open his house and would keep everyone’s spirits up. He was very good at motivating people, and he would come and visit us as we went around the country. Every so often he’d pick a place and he would come down to see us all and cheer us all on. He and his wife Anne. It was tremendous, hugely, hugely influential.

So that kind of opened up my creative world again, you know. It just seemed an easy thing then to move on to film, because I had been around actors so much, and the three women, we all had projects, like Anne had Mother Ireland. We wrote them down as part of our tendering process to Channel 4, and I wrote the idea for Hush-A-Bye Baby because I hadn’t written it yet, and it just seems like an incredible nerve now that I thought I could direct a film. But I think somehow working with Field Day gave me that confidence because I really liked being with actors. I felt like I understood them to a degree, that what they did was incredibly brave. It just gave me confidence and Brian gave me confidence. The other thing was that in Ireland at that time, these incredible things were happening in terms of the body politic all over the island. We had the Supergrass trials in the north in ’84, because I had set the film in ’84, and in ’83 with the abortion referendum which was just the start of a nightmare series of decades of trying to fight back and then in ’84, Ann Lovett dying and the Joanne Hayes tribunal which was more like a trial. So, these all had a massive impact. They were very emotional times, very, very difficult times.

So, Channel 4 coming along was such a stroke of luck, it really was, because I think other people weren’t going to give us a chance to make films They would have spent their lives trying to keep you out of any kind of practice like that. The Northern Irish film sector was very unionised, but it was very traditionally unionised. It was very protectionist in the way it handled its policies, whereas this thing called the ACTT Declaration* enabled us. We were not treated that well by some other crews and filmmakers in the North. Later we all became friends because I started giving people work like. But no, we were not treated very well. And so, we would naturally look to the south, to filmmakers like Joe Comerford. That’s when I first became friendly with Joe. Joe, and also Bob Quinn was incredibly supportive, and Cathal Black. All of these people… Lelia Doolan. They all helped us. They were all interested in seeing what we were doing, because I think they just had a broader awareness. They thought anything coming out of the north was interesting.

Mentioning the southern filmmakers there, it got me thinking about how with the Workshop Declaration then there was also a new growth of radical filmmaking, radical TV in Britain. You’ve got the Black Audio Film Collective and different workshops. Were they influences on you as well?

Yes. We made connections with them for sure because the workshops were all kind of collectively a single body, so we would meet maybe at Channel 4 meetings. But we were apart in a sense because we’re across a sea, on a different landmass. But we were certainly aware of them and of anybody who had a film coming out on the Eleventh Hour. Our works were confined to what was called the Eleventh Hour on Channel 4 which Channel 4 commissioning editor Stuart Cosgrove later said was one of the most boring slots *laughs* on all of British TV. But that’s where the work would be seen and we would be very excited when a new film from a workshop was coming out and we would always watch them, you know. So, we were very aware of people like John Akomfrah, but half the time we didn’t understand what they were doing, we would go “What the fuck was that like?”.

And Amber Workshop up in [Newcastle-upon-Tyne] had been around for a long time before the Channel 4 workshop movement started. So, whereas we used the advent of Channel 4 to set up and to galvanise and to focus our feelings, they were there already. And they were all dealing with different things: some were Asian workshops, black workshops, gay workshops, trade union type people in the North, Amber would have been like that. Generally, of the left and socialist. I can’t think of any that you would call right wing. So, they were a thorn in the side definitely of the British establishment. So yeah, we were very aware of them. Often, we had friendships. But it was probably more the case for them living over there than it was for us. They were aware of us but there was more of a remove.

I would like to jump ahead a bit to the founding of Besom Productions in 1992. Did you see that as a continuation of the work you were doing with the Workshop?

Not really at the beginning because Channel 4 had cut our funding at Derry Film & Video Workshop in the year that Hush-A-Bye Baby first appeared at the Celtic Film Festival, which that year happened to be in Gweedore, and it won Best Drama, which was amazing for us like. It started winning awards, but they cut down our funding because we were so much trouble for them. We were always involved in controversy. Rod Stoneman, then Deputy Editor of Independent Film & Video for Channel 4, was a great personal support for us. He remains a friend to this day. He writes about that time, but we have totally different memories and views of what went wrong, it’s interesting.

When they cancelled the Workshop, I took a year to wind down our affairs. There were a lot of files and stuff, and I kept all the files. I wrote most of the funding letters. And it, [the behind-the-scenes documentation, stills and other files that went into] Anne’s work in Mother Ireland, and Hush-A-Bye Baby, became recently part of a project, a retrospective exhibition of Derry Film & Video entitled Open the book at a different page (2021-22) that was shown in the Project Art Centre by Sara Greavu and Ciara Phillips. And that amazed me, that people were interested in that, that it had become part of history, but I’m very grateful that I kept everything. It’s been hard keeping them over the years. I used to have a big office in town which I left just before covid 19 got into full swing and I had boxes and boxes of stuff, and lot of them are still in my house. So, the Irish Film Archive, I donated all of my Besom Productions tapes to them, and they have taken them and now they’re looking through the paper stuff.

So, Besom was… I didn’t form it for a couple of years because I was clearing up with Derry Film & Video and I did an odd little bit of work for other people like writing a little film about health for young people for the NI Government Health Promotions Unit. I created Besom thinking “I’d better do this now” but I was careful in the beginning because I felt I had been labelled, and even felt I was avoided by the BBC. I’m not sure of that but I sort of feel it. They never gave me work, but Channel 4 still gave me work, through their Schools Division. They had a company called 4 Ventures and it did programming for schools, and I thought education was a good thing to do. And I enjoyed doing those, so I did a few schools series, quite a few actually, on all sorts of different subjects. Even in that period I made another little drama which was about racism and sectarianism in Northern Ireland [You’re Looking at Me? (2003)]. It’s not seen very much because it’s got a didactic intent. And then I just gradually started bidding for other ideas, you know, that I wanted personally to make. And Fergus Keeling was at the BBC at the time, and he did respond. He did open his arms and took us in from the cold like.

That Channel 4 education branch doesn’t exist anymore. They stopped it because it was a free service they provided for schools and then they had to make cutbacks, so they cut it. My work was mostly then documentary, but it was reacting to what was going on around me like I made a documentary about the 25th anniversary of the hunger strike, [The Hunger Strike (2006)] which was one of the highest viewed programmes they ever had on BBC Northern Ireland. I also made one about Frank McGuinness [Clear the Stage (1998)].

I watched 12 Days of July—

That’s probably one of my favourite films, that one.

It’s remarkable for many reasons but one of them is that film usually takes a long time to gestate. There’s usually this delay with filmmaking, but this was made right in the middle of [the Drumcree conflict]

Yeah, we were pushed to deliver it very fast. Channel 4 had us on three stages of development, which was very unusual, because they couldn’t make up their mind if they wanted it. Liz Forgan, who was the director of programmes, eventually said “OK, but we want it within two weeks [of the Drumcree march event]”. But yeah, we were not news and current affairs. We didn’t have the team to do that. So, it was a very, very big pressure. I was barely sleeping while making that. I had to bring in my old friend and highly accomplished filmmaker Michael Hewitt and Dearbhla Walsh, the great Dearbhla Walsh, who’s doing so well now. But yeah, that was right at the cutting edge of what was going on, right on the frontline. That to me is real documentary because we didn’t know what was going to happen. We didn’t know what the outcome of that was. So that whole tension of waiting to see what decision Secretary of State Mo Mowlam would make, and the disappointment of the people in the community – because she came to visit them, as you see in the film, and they believed that her sympathy was with them and that she was going to come down in their favour. But I think she was shat on by the Policing Board themselves. They just ignored her. They just ran roughshod over her.

So yeah, that one, and Bloody Sunday was one that took me so long to make. I made it over a period over six years and then they went off to consider the report and they said it would take them 18 months. They said the trial would take 18 months and it went on for six years, and then they said the report would take 18 months and it went on for another six years. Oh, there was so many, many paths that the documentary took, in trying to come down to a storyline people might watch. And that was nominated for the Prix Europa, but it’s a heavy watch as well. Some of the films I did were pretty heavy watches *laughs*.

I would like to ask you about that film. It’s unusual in that you feature a lot in the film itself.

Yeah, that wasn’t supposed to happen. The way that happened was, I went to this training course called Eurodoc. It was split into two groups. There was an English-speaking group and then a French-speaking group. Carl-Ludwig Rettinger [later a producer on Bloody Sunday: A Derry Diary (2007-10)] headed up the English-speaking group. We had to travel around Europe to attend different stages of the course. The whole idea was that they would train you to pitch an idea. So, I brought this idea, and we had a final week of pitching in Nimes in France. My proposal got offers because, there were commissioning editors from all over Europe and they could make you a funding offer. They didn’t have to, we were just practising our pitch, but it was an opportunity for them to see new ideas and if they liked any, they would offer you funding.

I had four different commissioning editors offer me money to finish my film because I was really struggling to make it. I couldn’t get a single British broadcaster to put money into it. They just ignored me. I think part of their view was that I was too subjective because I had been there on the day as a witness and you know, they just didn’t trust what my point of view would be. They would have described it as propagandist, you know. That’s how they would have seen what people like me were doing. Everything had to be filtered through some very well accredited journalistic type of person like Peter Taylor. Nobody else could have been trusted to talk about the North even if you had experienced it. That was definitely the view. It was very colonialist really.

But suddenly I had all these people in Europe wanting to help make my film. I was only allowed to choose one. I chose this lovely woman called Anne Evans, commissioning editor for [the German broadcaster] ZDF. She commissioned the film for the Arte Channel. She would come over to Derry to see how we were getting on with the edit and the edit was taking forever and the film ran over and of course the tribunal ran over. And at one point, it was such a mangled story *laughs* she couldn’t understand what was going on, until I explained it. She said “Look, the answer to this is, that whenever you explain it to me, I understand it. Why can’t you tell us in the film? Because you were there on the march on Bloody Sunday and audiences like that” And I reacted against it for the longest time but then they convinced me to do it. I’m quite shy in front of the camera, to be perfectly honest. I’ve got better over the years but then I wasn’t.

And I did it again for this one I’ve just finished, called Stolen. I’m not sure if it works that well either. But that’s how that happened. It was trying to filter it through the viewpoint of somebody who was there, to make it more personal really, try and guide an audience along instead of at a distance. It really became a trend around that time as well.

It never showed on British television, even though I sent it to Channel 4. They just ignored it. And then eventually I wrote an email to the new Head of Documentaries, Hamish Mykura, and I said “I don’t understand. I used to have a good relationship with Channel 4. I don’t understand why this has happened.” And he wrote back and said “Well I’ve just viewed your film and it’s competently made” but the report had come out at that stage, and he felt it was too late, which was nonsense, really was nonsense. They just wouldn’t show it like. It’s a film that, when it was shown on RTÉ, I probably had the most reaction in terms of people contacting me afterwards to talk about it and asking if they could see it again. It’s not my favourite film but I’m kind of glad I did it all the same. And Banty, who was my main character in it, Banty Nash, James Nash, he died there last year. You stayed friends with people a long time. So that’s why it’s important to get these witness statements while people are still alive, so you can tell their story.

Could you talk about your new film, Stolen? How did the project originate and develop?

Yes, Stolen was originally called Limbo, and I became interested in it when, like everybody else, I was reading about the stories, about what was happening. In 2017, the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, Katherine Zappone stood up in the Dáil and verified that evidence of human remains had been discovered in the playground at the former site of a mother and baby home there. And I thought, “She’s done it!’ We all were reading all this stuff about Catherine Corless and her having discovered the death certificates of 796 babies with no records of burial sites. So, I contacted her straightaway and asked would she be interested to make a film. And she was being inundated. I can’t imagine the pressure she was under both from people trying to trace their families and from press. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I didn’t do it in the way I intended to do it originally, from her point of view, because what I was intending to do was hard to explain. She was used to doing news and thought I meant I would do a few interviews and that would be it, but no, I wanted to go on a journey. But then covid 19 happened and everything changed.

So, this film is not like the usual film I make, where I do go on a journey. In the end, I decided just to let the witnesses, people who had experienced these things, to let them tell their stories, to give them a chance to put it on screen because lot of them had done it in the newspaper, but not in an overarching documentary. Basically, I talked to people from many different homes, because Tuam was not the only one and there were more people died in some of the other homes, like in Sean Ross Abbey Mother and Baby Home in Roscrea, County Tipperary. Over a thousand died there with no burial sites. And Bessborough in Cork was another horrific one again. No burial sites and in fact, where they may had been buried was zoned for development recently, but thankfully the government has turned that down. So, there’s lots and lots of unanswered questions out there.

Why did I decide to do it? I think it’s kind of a continuation of the work I did with Hush-A-Bye Baby. When I was doing Hush-A-Bye Baby, I took the story of a young girl at 15. It’s not a hugely dramatic story, it just refers to other stories. I couldn’t do the story of Ann Lovett because at that time nobody would talk, and I kind of didn’t want to because it was so raw. There’s lots of symbolic references in Hush-A-Bye Baby to it. But it was about how women were being treated on this island, and this is to me like a continuation of that. It’s a story of what was actually happening to women who dared to get pregnant outside of marriage, or found themselves pregnant outside of marriage, and how they were treated and how they were shamed. So, it’s like all these years later, over thirty years later - Hush-A-Bye Baby was a drama but this is about real women - this is what was happening to them, this how women were treated. I’m a feminist woman obviously, and my main preoccupation has probably always been about how badly women have been treated and how it has stop.

I always think I want to write another script. I’m getting on now so whether I will get the chance to do it or not is not certain, but what I want to do is a drama about the rage of women but try to make it funny *laughs* which is hard to do. It’s just appalling the way women have been treated on the island, like really appalling, and it’s great to see them all speaking out now. The way I look at it, theirs is an act of resistance. They’re resisting, speaking out against all that has happened to them, and demanding to be heard.

*Note: The catalyst of Harkin’s filmmaking was one of the most important events in the history of UK moving images. In 1982, the newly minted Channel 4, supported by the BFI and the Regional Arts Associations, brokered a deal with the traditional film and television unions to pull back their protectionist policies to allow for new streams of independent film and TV production. The ACTT Workshop Declaration allowed the formation of regional ‘workshops’ and as a result, a wellspring of formally and politically radical film and television work reached British television screens across 1980s. It led to the creation of groups like, just to name a few, Derry Film & Video, the Black Audio Film Collective, Sankofa Film & Video Collective and Retake Film & Video Collective, as well as the support of pre-existing outfits such as the Amber Film Collective in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and the Sheffield Film Co-Op.

You can explore Margo Harkin’s work at Besom Productions. Stolen screens with a Q&A with Margo on the 21st June 2023, at Queen's Film Theatre, as part of Docs Ireland.